INTRODUCTION :

The

warming of sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific causes changes in

Pacific trade winds and ocean currents, setting off a chain reaction of weather

disturbances worldwide. Scientists believe that Bangladesh is one of the most

vulnerable countries in the world to El Niño or La Niña effects.[1] The country experienced very adverse El Niño

effects in 1997-98, which included

severe drought in various places and severe La Niña effects in 1998, which

included the most devastating floods.

It is thought that the country was also affected by the 1972-73, 1976,

1982, 1986 and 1994 El Niño events.[2] The

country's geographical location and climatic characteristics made it vulnerable

to such warm events.

The

present study has been designed mainly to assess El Niño impacts and response

strategies in Bangladesh and to depict the scientific views about their

teleconnections. Both primary and

secondary sources of data and information have been used for the study.

Relevant organizations like The Space Research and Remote Sensing Organisation

(SPARRSO), the Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD), The Disaster

Management Bureau (DMB), the Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA),

concerned experts, and governmental/non-governmental officials have been

consulted. A seminar/workshop, comprising participants from concerned agencies

and from various government departments and non-governmental organizations, was

organized to incorporate a multi-dimensional approach to the study.

The

present report has been divided into five sections. Section-I deals with El

Niño/La Niña impacts in relation to

the country's geophysical & socio-economic settings, the existing

government mechanisms for dealing with the impacts of climate-related

disasters, and the country's level of scientific research on and historical

interest in El Niño. The flow of

meteorological information about the 1997-98 El Niño event, including the

transmission of El Niño information, media coverage, etc., has been depicted in

Section-II. El Niño teleconnections to various parts of the country area have

been scientifically analyzed and explained in Section-III. Section-IV deals

with the forecasting by analogy of El Niño/La Niña impacts. Section-V includes policy implications,

recommendations and conclusions.

1.1 GEOPHYSICAL AND

SOCIOECONOMIC SETTING

El

Niño (or La Niña) events do not affect all regions of the world with same

intensity. The vulnerability to El Niño effects depends upon the geographical

setting, whereas the intensity of impacts of the events depends upon both the

geographical and the socio-economic setting of a country.

1.1.1 Geophysical Features

Bangladesh

is a transition zone between Southwest and Southeast Asia. It forms the

capstone of the arch formed by the Bay of Bengal, and because of the Tibetan

plateau (massif) to the north, it is a comparatively narrow land bridge between

the sub-continent of India and sub-continent of Southeast Asia. More precisely,

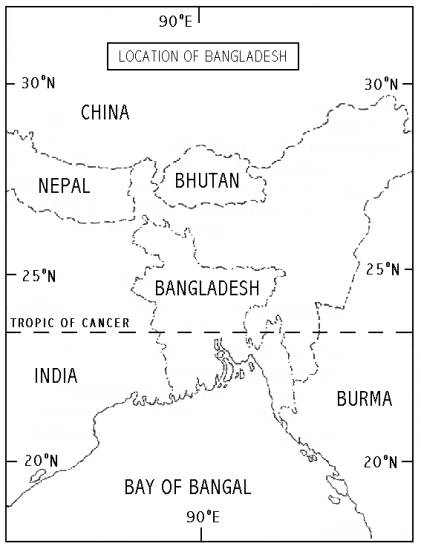

the country stretches latitudinally between 20° 34' N and 26° 33' N and longitudinally between 88° 01' E and 92° 41' E (Map 1). Some of

the biggest rivers of the world flow through the country and form the largest

delta in the world. The Ganges-Brahmaputra River system forms in the Bengal

Basin, a delta of 40,225 sq. km. in extent. It is, therefore, quite obvious

that the monsoon rains, the rise and fall of river levels, floods, alluvia and

dilluvia and changes in river courses form the substance of both the cultural

and physical geography of the area.

Geological

studies suggest that, due to continental drifts and plate tectonic movements,

the Gondwana part of the single continental mass Pangaea[3] underwent several changes through the

processes of subduction, collision and sea-floor spreading. In the Oligocene

Period (38 to 26 million years ago), some time after the plates collided, a

portion of the northern part of the Indian plate fractured and sank below sea

level. This portion was gradually filled up to form the eastern part of the

Bengal Basin (Map 2).[4] Bangladesh is, therefore, formed on a mass

of sediments washed down from the highlands on three sides of it, and

especially from the Himalayas, where slopes are steeper and the rocks less

consolidated. The greater part of this land-building process

must have been due to the Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers. It is mainly a deltaic

land having hundreds of big and small rivers, Haors (large lake-like bodies), Baors,

Bils, etc., all over the country and

some hills and mountains in the northeastern, eastern and southeastern parts of

the country. The country has the longest continuous sea beach in the world

(about 144 km).

Map-1

Source:

Rashid, Harun Er.: Geography of Bangladesh.

University Press Ltd., Dhaka, 1991, p.2.

A

vast amount of water (1073 million acre feet/year)[5] flows through Bangladesh of which 870

million acre feet/year flows into the country from India. This brings about 1.5

billion metric tons of sediments into the country every year.[6] The

climate of the country is characterized by high temperature, heavy rainfall,

often-excessive humidity and a fairly marked seasonal variation (i.e., tropical

climate). The country is very rich in bio-diversity.[7] Due

to its geographical location, landforms and a funnel-shaped seashore,

Bangladesh is considered to be one of the most vulnerable disaster- prone

countries of the world.

1.1.2 Socio-economic features

Bangladesh is an

agrarian country with 120 million inhabitants within an area of 143,999 sq. km.

of land. By religion, the country’s population consists of 86.6% Muslims, 12.1%

Hindus and 1.3% Christians and other cultural minorities. Nearly four-fifths of

the people depend, directly or indirectly, upon agriculture. The country's

agro-based production system depends mainly on climatic phenomena. High

population density, a rapid rate of population growth, low per-capita income

(only $273 US a year), mass poverty, low literacy rate, high rate of

unemployment, malnutrition (67% of the total population), weak economy, etc.,

are the major socio-economic features of the country.[8]

Bangladesh is an

agrarian country with 120 million inhabitants within an area of 143,999 sq. km.

of land. By religion, the country’s population consists of 86.6% Muslims, 12.1%

Hindus and 1.3% Christians and other cultural minorities. Nearly four-fifths of

the people depend, directly or indirectly, upon agriculture. The country's

agro-based production system depends mainly on climatic phenomena. High

population density, a rapid rate of population growth, low per-capita income

(only $273 US a year), mass poverty, low literacy rate, high rate of

unemployment, malnutrition (67% of the total population), weak economy, etc.,

are the major socio-economic features of the country.[8]

Many

of the people of the country have some deep-rooted religious superstition

regarding natural disasters. They believe that God imposes all disasters,

especially climatic disasters as a result of our outrageous activities.[9]

Map-2

Source:

Rashid, Harun Er: Geography of Bangladesh. University

Press Ltd., Dhaka, 1991, p.8.

1.1.3 Government Mechanisms

for Dealing with the Impacts of Climate-Related Disasters

To reduce the negative impacts of

climate-related disasters and minimize the sufferings of the people, the

Government has established a set of mechanisms including institutional

arrangements for disaster preparedness and relief and rehabilitation of the

area affected or potentially affected.

For making the established mechanisms appropriately and effectively

operative, an exhaustive guidebook entitled, Standing Orders on Disaster,

has been designed to outline the activities of each related ministry, division

and major agencies and departments.

Considering the importance of the effects of climate-related disasters

in Bangladesh, the government has also taken initiatives to formulate a

comprehensive National Policy of Disaster Management and a National Disaster

Management Plan. To deal with climate-related disasters by the entire

government machinery, the National Disaster Management Council meets the

requirement of clear policies and provides scope for proper implementation of

the policy directives. A High Level Inter-Ministerial Disaster Management

Coordination Committee gives decisions for implementation of these policies and

policy directives. The Committee incorporates the role of the Ministry of

Disaster Management and Relief as the responsible line Ministry, provides for

integration of the Armed Forces and reflects the crucial role of Disaster

Management Committees at Union, Thana and District levels. The

Bangladesh Cyclone Preparedness Program (CPP) has about 30,000 volunteers to

come to the rescue of the affected people in the coastal areas during cyclones.

The

Bangladesh Space Research and Remote Sensing Organization (SPARRSO) and the

Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) are responsible for providing

forecast information about climate-related disasters in the country. The Bangladesh Water Development Board

(BWDB) is responsible for forecasting water-related disasters like floods and

their possible impacts.[10] These

organizations are also responsible for conducting research about

climate-related disasters and their effects on society and environment.

The

government media, Radio Bangladesh and Bangladesh Television, play the prime

role in transmitting the forecast information, tracking the courses and

chalking out elaborate programs on awareness development about preparedness and

the possible effects of potential disasters. The National Dailies also play a

vital role in these respects.

1.2 Climate-Related and Other Natural

Hazards Affecting the Country

During

the 1997-98 El Niño event, climate anomalies with significant socio-economic

impacts were experienced outside the tropical Pacific. El Niño-related natural

disasters are of global concern, have their most severe impacts on vulnerable

communities, and can contribute to increasing poverty.[11]

Bangladesh

is perhaps the only country in the world where casualties due to a cyclone

could rise into the hundreds of thousands. Floods can devastate more than half

the country causing damage in the billions of dollars. Nor'westers and

tornadoes often demolish the economy and settlements in many parts of the

country. Droughts destroy the country's food chain, food reserves and agro-based

production systems. A large number of households become homeless as a result of

riverbank erosion. Earthquakes cause severe damage to human settlements. The

climate-related and other natural disasters affecting the country have been

listed below in order of concern:

· Floods

· Tropical cyclones and

associated storm and tidal surge

· Nor'westers and

tornadoes

· Erosion

· Drought

· Earthquakes

· Siltation

· Salinity

·

Desertification

Scientists

have found a correlation between El Niño/La Niña events and the variability of

climatic phenomena in Bangladesh. They

have suggested that further research needs to be undertaken in this respect.

1.3 Level of Scientific Research on El Niño

El

Niño (or La Niña) has drawn worldwide attention very recently. The world’s experts

have differences of opinions regarding the origin and impacts of El Niño or (La

Niña) events. Walker and Bliss (1932) believed that the periodic warming and

cooling of the southern Pacific Ocean, which produces El Niño or La Niña

effects, is actually related to a phenomenon known as Southern Oscillation.

According to their view point, "when pressure is high in the Pacific

Ocean, it tends to be low in the Indian Ocean from Africa to Australia; these

conditions are associated with low temperatures in both these areas and

rainfall varies in the opposite direction to pressure. Conditions are related

differently in winter and summer, and it is therefore necessary to examine

separately the seasons of December to February and June through August.”[12] The Southern Oscillation is a seesaw

oscillation of pressure in the tropics between the Indian and the West Pacific

Oceans on one hand and the Southeast Pacific Ocean on the other. This is an

atmospheric phenomenon, whereas El Niño is an oceanic phenomenon.[13] Bjerknes considered it to be an event of ocean-atmospheric

coupling.[14] An

El Niño event is basically manifested by a reduction in coastal upwelling of

cold, deep ocean water to the surface.

Some scientists have argued that this quasiperiodic appearance of warm

surface water in the upwelling regions is triggered by various factors such as

continental drift, tectonic movement of ocean plates, earthquakes or volcanic

eruptions on the ocean’s bed. Greenhouse effects and global warming has also

been interpreted as triggering factors of El Niño or La Niña event.[15] Some scientists explained it to be a

combined effect of southeast trade winds, variations of sea surface

temperatures (SSTs) and Coriolis Forces.[16] Von

Humboldt (in 1802) presented his Peru-Current Theory, which is popularly known

as the Humboldt Theory, to explain the event. Klaus Wyrtki tried to explain the

phenomena with his Equatorial Kelvin Wave Theory.[17] Mark Cane stressed the importance of Rosby Wave Propagation from

the eastern to the western Pacific.[18] Numerical experiments are being carried out on a hierarchy of

coupled models of the atmosphere and the ocean and encouraging results have

been obtained toward El Niño predictions.

Many

scientists had previously speculated that El Niño was caused by disturbances

along the earth's crust, since earthquakes and volcanic eruptions often

preceded the phenomenon.[19] But

new work with computer models and sophisticated monitoring equipment suggests

that the current is not triggered by geological disruptions. Instead, it is part of a naturally occurring

cycle resulting in the interactions between the sea and the skies of the

equatorial Pacific. Scientists say that

the latest monitoring efforts have helped them make more reliable El Niño

predictions. Some scientists think that the decrease in tropical cyclone

numbers frequency and intensity in recent decades might be interpreted as

evidence that predictions of more and stronger cyclones accompanying warmer

SSTs are wrong.[20]

Scientific

research in Bangladesh relating to El Niño has not reached a satisfactory

level. Research on the issue is mostly conducted on individual

initiatives. The researchers use data

generated through both traditional and sophisticated methods by various

national and international meteorological agencies. In Bangladesh, studies have been conducted on "A

Climatological Study of Bangladesh and the Possible Correlation with El Niño/Southern

Oscillation" in 1993, "Bangladesh Floods, Cyclones and ENSO" in

1994, "Theory of El Niño" in 1994, "El Niño Southern Oscillation

and Rainfall Variation Over Bangladesh" in 1996, "ENSO and Monsoon

Rainfall Variation Over Bangladesh" in 1994, “El Niño and La Niña Cycle”

in 1998 etc., with individual initiatives. SPARRSO took up a research project

in 1999 entitled "Development of Models for Predicting Long Term Climate

Variability and Consequent Crop Production as Affected by El Niño-La Niña

Phenomena." Besides, several

studies have been conducted directly on the after effects of El Niño-La Niña

phenomena.

Through

these studies, scientists identified that the devastating flood of 1974 had

occurred due to the 1972 El Niño event, and the severe floods of 1987 and 1988

had occurred because of the 1986 El Niño event. They had predicted during the

1997 El Niño event that a La Niña situation could develop after May 1998 and

Bangladesh might experience severe flooding.[21] Scientific research found a negative

correlation with tropical cyclones over the Bay of Bengal and a correlation of

ENSO events with rainfall deficits over India and Bangladesh[22] during the 1951-87 period.

1.4 Historical Interests of

El Niño before the Onset of the 1997-98 El Niño Event

There

is no authentic historical record about when and how the first El Niño

occurred, but geologists assume that El Niño began occurring since the Tertiary

Period (2-65 million years ago).[23] Recorded historical evidence proves that the first El Niño event

occurred in 1925-26, although the term El Niño was not used in the record

(except in association with impacts in Peru). The term El Niño came into

worldwide use only recently. It is thought that El Niño has immense influences on monsoon climatic variability. Historical

evidence shows that monsoon phenomena have been under study on this

sub-continent since ancient times. For

example, monsoon phenomena have been mentioned in the holy Ramayana and

Mohabharata and in other Vedic books. In the book Artha-Sastra (Science of

Economics) written during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya (321-296 B. C.) by

his Minister Kautilaya, there is mention about the amount of rains at different

places, indicating that they had knowledge about rainfall measurements. The

astronomer Varaha Mihir (505-587 A. D.) used to predict rains. Astronomer Arya

Bhatta and Brahmagupta also studied the monsoon. The famous Sanskrit poet

Kalidas composed poems out of monsoon clouds as depicted in his Meghdoot

(Messenger of Cloud) and Ritusamahara (Cycle of Seasons). However, the real

credit for the meteorological and agro-meteorological predictions during the

ancient times goes to a mythical woman named Khana. Her verses are said to be

the envy of any scientist at any time. Scientifically Gilbert Walker, during

the time of British rule in India, identified effects of ENSO events in this

Sub-continent.[24] Sikka in 1980 was apparently the first to suggest that during El

Niño years the Indian monsoon performs below normal. Parthasarathy and Pant

observed in 1985 that the Indian monsoon shows a good correlation between a

strong SOI (cold event) and a good monsoon year.[25] Mandal conducted a study in 1989 on the relationship between

tropical cyclones and rainfall over the Bay of Bengal and ENSO events. Chowdhury

also conducted the same type of study in 1992. Ahmed in 1993 predicted that in

general the Bangladesh monsoon shows a decrease in rainfall in El Niño years in

all seasons.[26]

Today,

experts opine that the ability to accurately predict the coming of El Niño

could have a considerable impact on human development. After a scientific

study, ERFEN (Estudio Regional del Fenómeno de El Niño) experts say, "By

tracking ocean temperature, salinity levels and wind patterns, they can now

tell when El Niño is approaching several months before it hits South

America.” National Center for

Atmospheric Research (NCAR) Senior Scientist Michael Glantz says, "If you

can forecast El Niño, you can shed light on when to expect droughts and floods

in various countries."[27] Khana, Ghagh, Varaha Mihir, Ahamika Duck,

and Bhandori, etc., the most famous mythical persons in this sub-continent,

told of these conditions 3-14 centuries ago.

They did not utter the words El Niño or La Niña in their sayings, but

they rightly predicted the phenomena.[28] Khana's sayings are especially considered to be the most

important, most scientific and most talked about mythical worlds in Bangladesh

and also in this region. Some of her sayings have been quoted and analyzed as

follows:

Basically,

Khana's sayings are based on astronomical readings. She did not correlate her

forecasts to events like El Niño or La Niña episodes. Most of her

meteorological readings seem to be very much based on local weather. But

today's scientists found strong correlations between El Niño and La Niña

episodes and local climatic behavioral patterns.[29] What she told many centuries ago during the 9th lunar day of the

bright fortnight in the Bengali month of Ashar (June-July), “If the month of

Choitra (March-April) of a year experiences cold weather and the month of

Baishakh (April-May) is marked by storms and hailstorms and the sky remains

free from clouds, the year will receive sufficient rains; if rainfall is

torrential, the year may experience drought; if rainfall is intermittent, the

year may experience heavy flooding; if moderate rainfall occurs, crops will

grow in abundance and if the sky remains clear and bright during sunset on that

day, the year will experience salvation." Today's experts

have found scientific bases behind these predictions. She also predicted that:

If southwest monsoon winds blow at the beginning

of the year, the year will be marked by sufficient rainfall.

It

means that when the southwest wind blows from the Bay of Bengal, it carries a

lot of moisture and, as a result, plenty of rainfall occurs in summer (the

beginning of the year). Khana also predicted these climatic phenomena in

another way. Khana's predictions about

drought were the following:

If southern winds blow during rains, the rain will

stop and flood will decrease.

Bhandori,

another mythical person of this sub-continent predicted as follows: “If Southwest winds blow for seven days

continuously, the country will experience severe drought.” But Khana's

forecasts directly about drought were as follows:

If the sky remains cloudy during the day and

clear at night, the country will experience drought.

If hot weather in the month of Poush

(December-January) and cold weather in the month of Baishakh (April-May)

prevail and heavy rainfall occurs at the beginning of the month of Ashar

(June-July), the months Shraban-Bhadra (July-September) will experience drought

in that year.

Khana

had very peculiar insights about the duration of rainfall in different seasons

of the year. According to her:

If it is foggy during the month of Poush

(December-January), there will be rain in the month of Baishakh (April-May) for

the days exactly corresponding to the number of foggy days in Poush; if rain begins

on Saturday, it will continue up to seven days; if it begins on Tuesday, it

will continue up to three days.

Varaha Mihir also

predicted these climatic phenomena in a different way: “If the month of Poush

(December-January) does not experience excessive cold weather, the year will

receive sufficient rains.” According to

Khana, "by observing the weather of the month of Poush (December-January),

the weather of the whole year can be predicted. The weather condition of the

first two and a half days of the month of Poush (December-January) is the

indicator of every month of the next year.” She had devised a process of

predicting a weather calendar, which, today, is considered to be very much

scientific in nature.[30]

Some other predictions

of Khana about floods, rains and agricultural production were as follows:

If Northern wind blows

during the month of Shraban (July-August), the year will experience severe

floods.

If rain occurs in the month of Choitra (March-April) and cold

weather prevails in the month of Baishakh (April-May) in a year, scarce

rainfall will occur in the new year.

The more the mangoes grow, the more the floods

will occur; the more the jack-fruits grow in a year, the more the paddy will

grow in that year.

It

is true that the scientists on this sub-continent did not correlate the

climatic phenomena to named events like El Niño or La Niña historically, but

they predicted and recorded them. These

days, scientists are well-equipped with modern tools and technologies to

predict future events and trace out the correlations of past events. It is

remarkable that the great Bengal famine years of 1770, 1940-41, 1943 and 1974

were El Niño years.